In my peripheral vision the smooth yellow, orange, and blue line flows effortlessly past the windscreen, indicating I have found the place I have been looking for. It is all starting to make sense. And from the angry snarl spitting into the atmosphere from under my right leg, we are beginning to pick up speed. Holding second gear as the bike goes from hard left to hard right with less than a thought, the brightly colored line of perfection now rolls passed the other side of the fairing. From somewhere in the ether, other world powers are now communicating with my right hand as the instant increase in decibels coincides perfectly with the front wheel’s exit from the smooth, Spanish tarmac. This means the inline, four-cylinder engine has hit twelve thousand rpm and with the bike still leaned over, we hurtle towards turn four.

Chopping the throttle to bring the front wheel back to earth, I can read the number 27 on the back of Stoner’ bright red Ducati Desmosedici GP 07, and putting all my faith in the sticky Michelins, I brush the brake lever and tip the bike on its side. Picking up the throttle my eyes are glued forward as I attempt to give chase. He is starting to pull away and there is nothing I can do about it. But just knowing there is a human being in the Ducati’s saddle finally brings me the thin thread of reality I have been looking for since I climbed on board Valentino Rossi’s Yamaha YZR-M1.

With whoever is riding Stoner’s Desmodieci obviously being another journalist, as witnessed by the fact that I am almost able to stay with him, I have finally found some way to gauge how fast the guided missile between my legs is traveling.

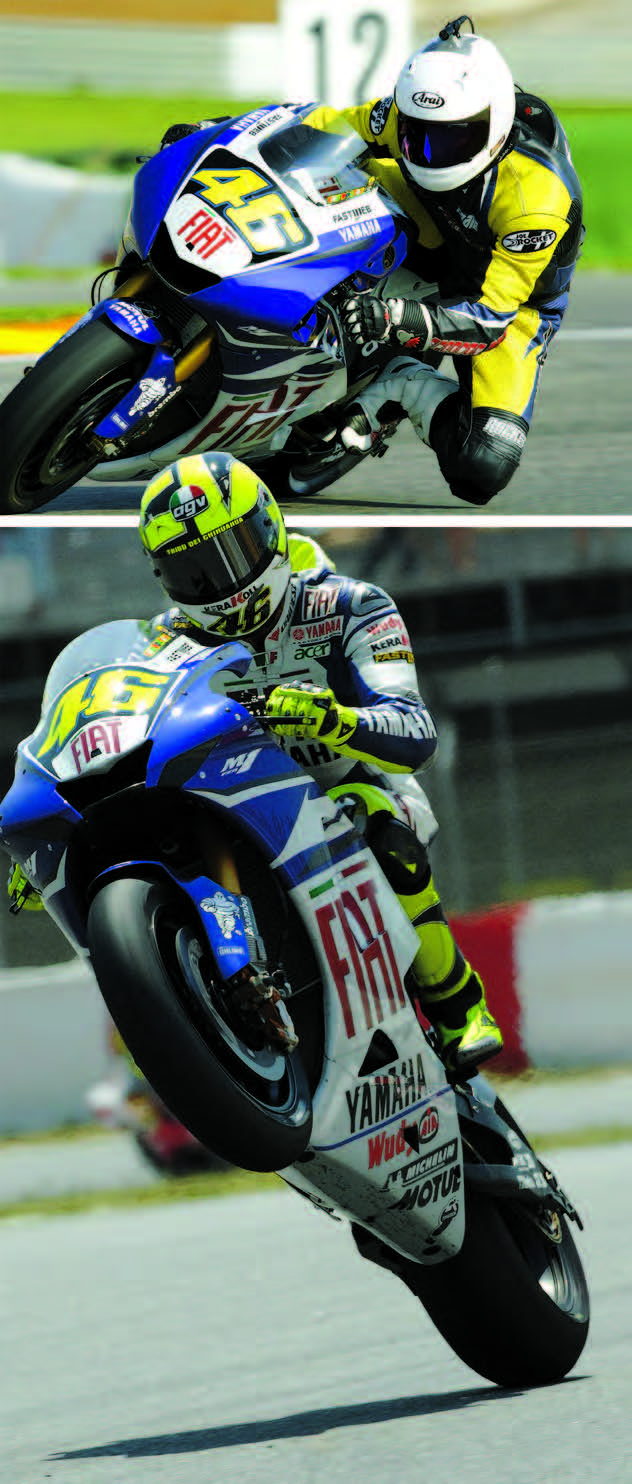

For the second time in my career, Yamaha has invited me out to Valencia, Spain to ride Valentino Rossi’s world famous Yamaha YZR-M1, emblazoned with his trademark number 46 on the carbon fiber bodywork. In traditional fashion, all the MotoGP teams have opened their pit doors for an assortment of journalists to sample their machines after the last race of the season. The term journalist should be used loosely. In reality, a high percentage of the test riders present are ex-racers turned part time scribes, shipped in to give their respective magazines the highest degree of exposure for their stories. For instance, there was some bloke called Kevin Schwantz in my group riding Rossi’s bike, just in case I wasn’t intimidated enough.

Having lost my MotoGP virginity on Valentino’s World Championship winning 990 back in ‘05, I was able to approach the new 800cc machine knowing I might live to tell the tale. The new 800cc M1 is making a tad less horsepower than the 240 claimed for the 990, but I wasn’t actually able to obtain an exact figure. According to the Yamaha factory race site, the bike produces over 200 horsepower, and chatting with various people in the pit garage during the test that figure is actually very close to the 990s output. What I can say is the 800cc engine is revving higher and producing less torque, so from a rider’s perspective there is a noticeable difference.

Like its predecessor, the new M1 uses an inline four-cylinder engine with a 90-degree crankshaft and four valves per cylinder. Weighing in around eight pounds lighter than the previous engine, it is also narrower as well as revving higher. Cradled in a twin-tube aluminum frame, this particular piece of modern artwork has multi-adjustable steering geometry, wheelbase, and ride height, while using a fully braced aluminum swingarm in the rear. Front suspension is a set of fully adjustable Ohlins inverted forks, which probably cost more than a starter home. In the rear, an Ohlins shock works through a rising rate linkage and has to be the sexiest piece I have seen to date on a motorcycle. As with its predecessor, the M1 rolls on 16.5-inch wheels, and these are available in a variety of rim widths depending on the track. These, as most of you will know, come wrapped in Michelin race rubber.

Brembo supplies brakes on the M1, and the system uses radial mounted four piston calipers biting down on 320mm carbon discs up front. In the rear a single 220mm steel disc is used and gets cozy with a two-piston Brembo caliper when Valentino puts his foot down. During my test, I never touched the rear, but have some interesting things to say about the front brakes in a moment.

Magneti Marelli, as with the 990, provides the electronics, and the mapping is fully adjustable. Coming with a host of sophisticated electronics, which include traction control, engine brake control, and torque control, the bike is also said to have more precise fueling this year. Watching the Yamaha techs prepare the bike in the morning, I noticed them changing out a black box under the seat and hooking up another electronic gadget in the front fairing that had “Estoril GP” on the side of it. Presumably, Valentino Rossi’s M1 was being set up for the softest power delivery possible and was having its red line turned down in an attempt to preserve it as much as possible. Although walking back into the pit garage 30 minutes after the testing began, watching the tech ripping off shredded bodywork and bent levers, it appears they didn’t soften the power delivery enough for one enthusiastic gentleman from Japan.

Introduced in an attempt to slow MotoGP bikes down, the 800cc limit imposed this year hasn’t reduced race times at all, and in many cases the new bikes are going faster than the old. Contributing factors are later braking points, faster corner speeds, and better electronics controlling the wicked amounts of horsepower these machines are producing. Watching and listening to the bikes before my ride in the Valencia sun, the brutal ear drum shattering noise they produce, and the way they seem to break the sound barrier approaching turn one, it doesn’t seem they have had their fangs trimmed so badly.

Sitting in the changing room pulling on my leathers, it’s ‘70s night in my stomach with the butterflies donning platforms before head banging to some serious Black Sabbath under my navel. Thankfully, by the time I arrive at the pit garage the concert’s over, and I have my mind clearly on the job. In a unique move, Yamaha has invited a very small number of people to ride Vale’s bike, so we get a total of ten laps in the saddle, split into two five lap stints. This is a much better than last time when I had one out lap, wo flying laps, and an in lap.

Watching the Yamaha mechanic ready the bike, I am surprised when he calls me over and shows me on the brake adjuster how to change it on the fly. Last time the guy just yelled, “you crash it we’ll kill you.” I assure him I will be too busy to need any changes, but do take the time to check the adjustable front lever position that seems fine for my digits. Watching the bike being started signals it’s time to go, and I climb into the saddle of possibly the world’s most famous race bike. Blipping the throttle lightly to test the travel, while the mechanics remove the wheel stand, I have a quick look around the digital tach and get myself as comfortable as possible. Up for first on the GP shifting six-speed box and off we go down pit lane. Like the 990, first gear is extremely tall. The bike doesn’t need much work to launch and ripping down pit lane with the sound from the Akrapovic pipe bouncing off the pit lane garages, it’s time to work.

Rolling onto the Valencia tarmac, with only four laps experience at this particular racetrack, I try and relax to figure out which way the circuit is going. Twisting the throttle toward turn two, it is quickly apparent that the 800cc engine doesn’t have the same brutal torque of the 990and tipping it into the turn, the bike doesn’t send me into a manic series of steering corrections. Feeling more neutral than the 990, as well as less likely to catapult me through the next gravel trap on the throttle, goes a short way to calming my nerves as I putter around the Valencia circuit.

In the saddle, I am very tense and oh so overly aware that binning the bike is not an option, so I elect to use my first five laps wisely. Learning the track, feeling the pull of the engine, and experimenting with the brakes, I am soon tipping into the last corner before the front straight. Knowing I survived a full throttle assault on the 990, I twist the throttle gently to the stop and get instantly greeted with a face full of windshield. Snapping the throttle shut and clicking down to second gear the resulting wheelie is less intense, but not so the forward motion. Hurtling towards turn one, shattering my mental perceptions with its mind-blowing explosion of speed, if the 800cc engine is any slower there is no way in this world I can tell the difference. Clicking down again and feeling my blood freeze from the resulting sonic boom emitting the four-into-one pipe, the time it takes to reach my braking markers is just plain sick. Thrashing a liter bike on a long straight you feel every gear change, and there is time to register what is happening. On the M1 it is all over before you can think, the bike causing the most vicious assault on the senses. Between the noise, the wind, and the rush of the asphalt beneath the wheels, the experience simply takes your breath away.

Rolling off in plenty of time, the biggest surprise of the test was the brakes. Having nearly given me a heart attack two years ago with their reluctance to operate without heat, and then behaving like someone had welded the pads to the disc when they did work, this year’s braking system is more similar to a modern sportbike than I could have imagined. Giving smooth, strong, controllable power, I was able to slow in plenty of time without any drama, concentrate on the corner, and re-opening the throttle. Running harder into turn two, I tried the brakes again to make sure it wasn’t a mistake and was rewarded with the same easy to use feel. Now don’t get me wrong, the stopping power is on the nose bleed side of powerful and makes yanking on the new ZX 10R’s brakes from 180 mph look like you are using a drum brake set up, but it’s not overwhelming.

Pulling back into the pits after my first five laps, I felt as stiff as a board from being so tensed up, and wandered how long I had gone without breathing. Instantly whisked away to Rossi’s chair; I had a chance to chat with Jeremy Burgess. With all the noise and confusion it wasn’t a long audience, but he did tell me that Yamaha needs to find some more power for next year. He didn’t want to get drawn into a tire discussion though. Leaving me to feel unworthy in the number 46 chair, the next person to sit down was Mr. Kevin Schwantz. With Kevin lapping some 18 seconds faster than me, there wasn’t much point in swapping notes, but he was definitely having a blast testing all of the assorted MotoGP bikes.

Heading out for my second session brought the most frustration I think I have ever experienced on a motorcycle. Feeling more relaxed, the bike making some sort of sense, and with a basic idea of the track layout, the laps got easier and easier. Then finally on the last lap, it all clicked as I chased Stoner’s Ducati. Comparing times, I lopped four seconds off lap four compared to lap three, and watching some video afterwards, I was visibly quicker on lap five. The frustrating part of this equation being that it was my last lap before bringing the bike back to the pits so I never got a time. The Yamaha M1 just wants to be ridden hard, and it takes a lot of minerals and seat time to conduct that task. But on the last lap I was beginning to understand what makes this bike so incredible, and my lap time on lap four was six seconds faster than on my best time on the 990. Although compared to Vale, the difference in speed is a like a snail getting a tail wind.

But lap times aren’t really the point of this test. I was given the ride so you the reader would be able to relate. By giving us ten laps this year, I unraveled some of the M1’s mysteries and got from shock and awe to looking at the tachometer long enough on the straight to realize the engine is spinning to over 18,000 rpm. I also found the sweet spot at 12,000 rpm where things really get crazy and to experience the bike howling forward with the front wheel off the floor when leaned over. And it also gave me yet another chance to take my hat off to the super humans who ride these machines and the whole Yamaha team of designers and engineers who produce one of the fastest race bikes on the planet. It might not have won a world championship this year, but it wasn’t too far off when you look at the teams competing. And with Rossi on better tires next year, Jeremy Burgess and crew looking for more power over the winter, it looks like the ’08 season is going to be plenty exciting. I am just hoping Yamaha keeps me on the invite list as I know with a few more laps I can really get that thing flying.A bit like a snail getting a tail wind.

— Neale Bayly

Photos by Yamaha